Ursula Martius Franklin was a Canadian physicist, metallurgist, writer, and activist working on technology and society, nuclear disarmament, urban governance, and the protection of humane ways of life. She’s one of my all-time favorite thinkers about both the obvious and obscured parts of our technological world. Her Massey Lectures, presented originally as The Real World of Technology and later collected and substantially expanded in text under the same title, are a genuine delight—generous and incisive, funny and sharp—worth listening to and then reading, or vice versa. Ideally you'd do it with a notebook at hand to ease the process of following strands of thought from Ivan Illich and Michel Foucault, Jane Jacobs and Fritz Schumacher, Max Weber and Norbert Wiener, all strung together with Franklin's drily funny kitchen-table feminism, always insistently grounded in the specific and the material.

I think many devotees of Elinor Ostrom and Christopher Alexander, in particular, will find a lot of joy in Franklin’s work. I find her almost uniquely energizing, not least when she pauses mid-gallop to explain why she must dramatically widen the scope of her inquiry to understand the technological present:

I would like to understand better the human, social, and ecological impact of technology; i.e., the way things are done. The deeper questions of time, space, and the meaning of meaning I must leave to philosophers and theologians. There is no contribution that I can make to their disciplines. I just worry about what happens to people, to their communities, their culture, their land, and their future under the weight of the new practices. I want to understand, as well as I can, this new real world of technology, because that is where all of us live.

—The Real World of Technology, Chapter VIII, emphasis mine

Another thing about Ursula Franklin: She was born in Munich in 1921 to an art historian and an ethnologist. Her mother was Jewish. She survived eighteen months in Nazi forced-labor camp followed by near-starvation and constant threats of violence in the months leading up to the war’s end and the years that followed it. I include this because I want you to know that when Franklin writes about fear and arbitrary power, she speaks with the authority of experience.

I hope to return to her ideas many times, but right now I just need to begin. And I want to begin with something that might seem too wispy, too un-ambitious, and especially too small for this moment.

Ursula Franklin's lifework was highly practical. As a metallurgist, she studied the structure of ancient artifacts to produce knowledge about the cultures that made them. As a peace activist and conservationist, she practiced civil disobedience and obstruction as well as healthy renewal. As a far-sighted thinker about modern technology, she worked relentlessly to lay the foundations of ways to think together that could produce better technologies—and to define what “better” meant. Maybe starting with this small way into her work—a single list for thinking about decisions—makes sense.

The list

Toward the end of The Real World of Technology, Franklin offers a casual and unfussy checklist for evaluating public projects and funding:

Should one not ask of any public project or loan whether it: (1) promotes justice; (2) restores reciprocity; (3) confers divisible or indivisible benefits; (4) favours people over machines; (5) whether its strategy maximizes gain or minimizes disaster; (6) whether conservation is favoured over waste; and (7), whether the reversible is favoured over the irreversible? The last item is obviously important. Considering that most projects do not work out as planned, it would be helpful if they proceeded in a way that allowed revision and learning, that is, in small reversible steps.

A modest list, though bigger on the inside than the outside. Many of its items refer back to ideas Franklin wrestled with earlier in the lectures and book, and I want to put them in context here as a way of walking especially new readers into her way of thinking. A confession: I began writing with the intent of producing a nice short post with just the list and a few thoughts about each item, but then my kid was home sick and then I wrote more to learn what I really thought and apparently there’s more here than is reasonable to cram into one post. So this one will be about just the first item, under which all the rest are sheltered.

Justice

As we consider daily, local, or world issues, the very central thing justice demands is that all people matter, and that all people matter equally. (From Ursula Franklin Speaks)

Justice, for Franklin, is both a necessary condition for peace and a foundational practice for democracy—and for technologies that support human flourishing. It’s the way out of life-denying systems and the local and planetary tragedies of categorizing real harms as externalities or just acceptable trade-offs. And it requires curbs on power:

Central to any new order that can shape and direct technology and human destiny will be a renewed emphasis on the concept of justice. The viability of technology, like democracy, depends in the end on the practice of justice and on the enforcement of limits to power. (From The Real World of Technology)

But just eliminating something that produces fear doesn’t genuinely work toward justice or peace if it ratchets up someone else’s terror. As Franklin said, “There’s no way to be secure when others are more insecure; there’s no way to reduce fear through means that make the burden on others greater.” (This is from a speech, “When the Seven Deadly Sins Became the Seven Cardinal Virtues,” collected in Ursula Franklin Speaks.)

This is an uncompromising position: It refuses collateral damage. It insists on doing the very hard and often tedious work of incremental improvements across an entire system—I think again of Christopher Alexander's process-centric systems work here, especially as it appears in his later thought. Maybe Franklin’s position also seems detached from the decisions we have to make to move toward better networks, but I think it’s centrally relevant. We live out the belief that people matter, Franklin said, “by giving people opportunities, providing education, providing a space for them to show what they are capable of, or providing that bit of shield and shelter needed for them to come into their own. That work, I think, is a caring function of justice.” (This is “Seven Deadly Sins” again.)

And you only get a real sense of justice, Franklin writes, if you “put yourself in the position of the most vulnerable, in a way that achieves a visceral gut feeling of empathy and perspective—that’s the only way to see what justice is.” We are all vulnerable to what Franklin might call indivisible harms: pollution, climate change, nuclear war, pandemic disease. But she speaks frankly about extending our perspective to people who are afraid for highly localized reasons: “our sisters and brothers who have reasons to fear the knock on the door at night.” (Same speech.)

There’s always a kind of sleight-of-hand at work in authoritarian power-grabs: They employ overblown and obviously dishonest surface attacks on the most laughably inadequate institutional performances of justice (and on the newest little flowerings of social change) as cover for much deeper attacks on the heart of democratic and just societies: real equality of opportunity and liberty—including the ability to participate equally in governance—protected by genuine curbs on the arbitrary exercise of power. Those principles are the actual targets.

That the pursuit of real justice is now under open attack by the resurgent oligarchy currently steering the federal government of the United States is a testament to the power of that pursuit. For Franklin, working within a long tradition, it is the only path to genuine peace.

Justice in our systems of communication

Franklin’s insistence on putting the realities of the most vulnerable at the center of decision-making is maybe the most radical part of her technology thinking—more radical when she was alive, less radical-seeming for a few years when artifacts like Sasha Costanza-Chock’s Design Justice emerged, and now an idea under concerted and overwhelming fire. This principle never made it into the heart of technology thinking, though, even when technology companies talked a slightly better game. The speed with which tech giants and their mid-tier hangers-on have jettisoned their commitments to, say, slowing down genocidal messages or blocking even a fraction of violence-encouraging speech from reaching its targets makes the underlying reality quite clear.

But I can think of no better central principle for people who want to make, repair, and use better alternative systems of communication and collaboration and communion than Franklin’s tradition of justice, which works to eliminate the conditions that produce justified fear and is grounded in real understanding of those fears and the conditions that produce them. The most vulnerable people go in the center. Their real and varied perspectives—not the ones we assume they hold, or the ones that a single token representative espouses—form the boundaries of acceptable trade-offs.

That this kind of network making and thinking is complex work—that it will involve mistakes and failures and upsets—doesn’t make it less vital. I keep returning to Franklin’s formulation of justice as care: “giving people opportunities, providing education, providing a space for them to show what they are capable of, or providing that bit of shield and shelter needed for them to come into their own.” The chance to build and repair and maintain conditions for life online that can help build and repair and maintain life offline is the whole game. It’s what most of us came for and stayed to work on.

If this seems impossible in the face of {{{everything}}}, maybe returning to some of Franklin’s most pragmatic and mischievous prescriptions will put a little breath back into your body, as it does for me.

Writing about the pressure in education to replace people with machines (in 1996!), Franklin writes, “In response to such pressure, I think, there is absolutely no solution except solidarity and pigheadedness: a recognition that some things are negotiable and some things are not.” (That’s from “Using Technology as if People Matter,” collected in Ursula Franklin Speaks.)

And: “To proceed in a hostile world, call it an experiment. Admit that you don’t know how to do it, but ask for space and peace and respect. Then try your experiment, quietly.” (From an interview excerpted here.)

Ursula’s human voice

Something I’ve failed to get across here is that in addition to being so astute and staunchly ethical and grounded in specifics, Franklin is extremely funny and irreverent and warm. Her Massey Lectures (available for free) have got me through bad times in the past, and I’m listening to them again this week.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorite bits of her work, from an address to the Woman and Peace Conference in Toronto in 1994 (collected in the Reader):

Peace is the absence of fear. Peace is the presence of justice. Because of the work that all of us have done, we are very clear that peace, in fact, is a consequence. Peace, as it was defined in 1936 by R.B. Gregg, “is a by-product of the persistent application of social truth and justice and the strong and intelligent application of love.”

Carve it over the doorways, Ursula. Write it across my palms.

Gratitude & notes

To say that I’m grateful to the folks who have signed on to support my work is a gross understatement. Thank you. (If you’d like to join them and it’s financially fine for you to do so, you can read more about that or sign up here. All the essays and research will always be free.)

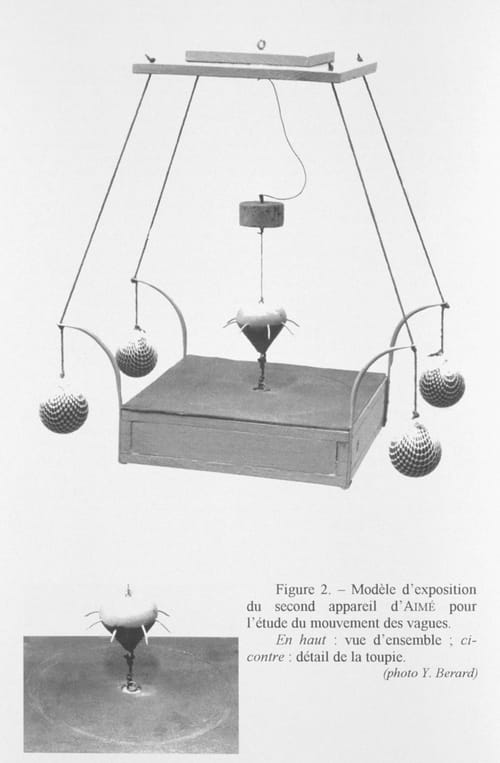

Thanks to NOAA for the digital collections that included this post's feature image: “Display model of Aime's second wave study instrument built in 1839 and tested in the anchorage at Algiers in 40 meters water depth for one month. This gave negative results even during periods of poor weather.” May I live up to its example.

And thank you, NOAA staff, for all of your efforts to keep us informed and alive.