I spent the spring and summer of this year talking to people who run Mastodon and Hometown servers with Darius Kazemi, and in the findings report we published about that research, I worked to emphasize the unique gifts of the fediverse’s current configuration.

The rarest and best of these gifts, in my view, is that if they’re motivated, tooled up, plugged into communities of support, and connected to their members' needs, small and medium-sized fediverse servers can provide context-sensitive, high-touch local moderation and adjudication for their members—while also making available connections to a broad landscape of other well-governed servers.

No matter what policy changes they make, centralized platforms will never be able to do this. Not because they don't want to (they don't) or because they tend to be run by damaged personalities (they often are), but because they can't. Nothing I’ve ever seen on the internet has suggested to me that if you replaced every petty tyrant and callous profiteer in those companies with someone better, genuinely good moderation would become possible at global-platform scale. (I don’t think a Meta-scale company could do good moderation even if they ploughed 30% or 50% or 90% of their profits into it, though I’d be delighted to see them try.)

But a server with 100 or 1,000 or 10,000 members run by steady-handed people who know what they’re getting into and are determined to make a good home for a given community? I know that can work; I’ve seen it done. Connect that kind of server with other well-managed servers and you’ve got yourself something less like a platform and more like Kropotkin’s free cities (probable ahistoricism notwithstanding). The work of maintaining those connections and pruning the network is inescapably and messily political—but then, so are the platforms, despite their increasingly baroque attempts to deny reality.

Here's how we put it in the report:

The server teams we spoke with have varying moderation ratios, but many provide more than one moderator per 1,000 members; the most lightly staffed server provides one moderator per approximately 1,800 members, and several provide at least one moderator per 100 members.

To put the above figures into context, in 2020—the most recent year for which we were able to find statistics—Meta employed or (mostly) subcontracted about 15,000 moderators to moderate content across both Facebook and Instagram, according to a report by the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. That same year, Facebook had 2.8 billion monthly active users(MAUs). Meta doesn’t publish official Instagram user numbers, but according to CNBC reporting, Instagram had approximately 1 billion MAUs in 2018 and 2 billion MAUs in 2021. Even if we use the older, lower number, Meta would have been providing only one moderator per approximately 250,000 active users across its two largest platforms in 2020.

For the thoughtfully governed, medium-scale servers represented in our sample, it’s possible to maintain a dramatically better ratio of moderators to active users even with a handful of moderators. Equally importantly, it’s possible to build moderation teams that are representative of a given community, and which are focused on moderating according to the specific concerns and norms of that community, rather than on enforcing one-size-fits all “community guidelines” delivered by a centralized organization.

This quality of the fediverse is more potential than real right now—there are some fantastic small and medium-sized servers (and even some good surprisingly large ones!), but to welcome a lot more people, the fediverse is going to need more well-governed spaces and more spaces designed to meet the needs of communities that aren’t well served on today’s fedi. The governance research we did was aimed at people working on both of those things.

But also, in the meantime, people are joining the fediverse and trying to join the fediverse and not necessarily finding those places that can be exceptionally well-governed homes. So that’s a thing I’m digging down into this winter.

Finding good homes

Getting people without existing connections on the fediverse to good fediverse series is currently difficult, as I covered via a mortifyingly extended analogy about badly fitting shoes in the intro post for this series. To be briefly less figurative, I want to relate my own path onto the fediverse.

I’m a reasonably technical person with a longstanding desire to be able to talk with my friends and participate in online conversations without being subject to centralized platform mechanics and their terrible influence on group behavior. I am, in short, a solid candidate for a fediverse account. It took me four years and four servers to get properly onto Mastodon: three moves away from server implosions and one move from a stable server to another stable server with stronger blocklists. Now it works great! I made it; I only had to lose my posts, threads, and private messages three times.

As ways of welcoming in new members go, that’s less of a user flow and more of a crime scene, despite the obvious good intentions of the various server teams. (I could, of course, have tried harder, I was preoccupied by work and health and life problems that weren't alternative social media networks.)

Other people have faced much worse welcomes. I’m haunted by the posts I saw from a gay man on Twitter who enthusiastically signed up for an account on a local Mastodon server where he was immediately swarmed by openly Nazi accounts that called him a pedophile and flooded his timeline with messages telling him to kill himself. And by the documented instances of Black fediverse members posting about race from reasonably well-regarded servers and receiving replies any reasonable observer would classify as hate speech.

All these bad experiences stem from failures of governance, and specifically of governance tooling and communication: The servers hosting these members didn’t block enough bad actors before they could do damage. This often happens not because the admins don’t care, or even because they’re technically inept, but because the tools they have access to require continuous manual effort—and, maybe more importantly, access to rapid info-sharing about bad actors, often in unpublicized, informal backchannels. (Sometimes it happens because server admins genuinely don’t care, or indeed enjoy and promote abuse themselves.)

But they also happened because those people didn’t find the right server for them—one that was hardened against specific kinds of attacks and ready to welcome them in.

Mismatches, mis-fits

Most governance failures manifest as mismatches: If a server shuts down because its single maintainer is overburdened or entangled in in-group battles or both, I would argue that that’s not even necessarily a failure of governance, unless the people on the server didn’t understand at the outset that this was a risk—or even a likelihood—given that server’s way of governing and sustaining itself. But if the server's members don't understand those inherent risks and aren't prepared to deal with them, it's probably a bad match.

Even my own bumpy entry into the fediverse came down to a mismatch between a.) what I was looking for as an outsider (someplace to hang out and be in community with people online in the way I’d done it in older ages of the internet), b.) what I discovered I needed to look for as a halfway-insider (a stable server governed by a team that practiced intensive moderation), and c.) what the servers I picked at nearly-random could offer.

This is true for all kinds of fediverse-joining failure modes:

- Mismatches between how a server handles local moderation and how a human on that server wants or needs to communicate, as when someone who wants to post nudes gets suspended by a server that doesn’t allow it or someone who wants to post their vigorously argued political views on a server that finds those views repugnant or uncomfortable.

- Mismatches between a given fediverse member’s risk profile and a host server’s willingness and ability to aggressively defederate from the servers most likely to direct abuse at that member (or, in some cases, from servers that handle obvious-to-them abuse but don’t address more complex social issues or communication subtleties).

- Mismatches between people who don’t want to lose all their previous conversations and start over on a new server every 6-12 months (even if they can bring their social graph along) and servers that rely for their stability on one or two people who are burned out by the work or overwhelmed by offline life or who experience interpersonal and coalitional problems that make running a fediverse server unsustainable for them. Most of the servers I’ve seen dissolve in the past several years have run for more than a year, but the problem is cumulative for orphaned members who, as they migrate to new servers, can end up experiencing multiple shutdowns in a limited timespan.

There are fixes underway for the tooling and communication problems that produced these terrible experiences, both within Mastodon and from independent efforts, especially at IFTAS (Independent Federated Trust & Safety).

Fixes for the mismatch problem, on the other hand, remain frustratingly out of reach. And the problem hits some people much harder than others: It's maybe not so hard to find a server that will work for you if even you’re someone perceived as especially well-suited to the existing fediverse. But if you’re a marginalized person posting about, say, identity-based harassment—or, to pick one we heard about a lot from server teams over the summer, if you're posting about a subject as heated as Israel and Gaza—you’re likely to have a bad time if you don’t have a home server with local norms that both permit your speech and moderate attacks by people who see you as a target to be discredited and silenced.

This uneven distribution of the fediverse’s gifts is an excellent reason to work on filling the gaps, but also to simultaneously help people with needs that can be met on today’s fediverse find the places where they’re most likely to be met.

Governance defines the fediverse

But maybe you’re still not sold on my central claim, which is that governance is the single most important factor in server selection, which is fair. Let's dig in.

In the big fediverse governance research project I worked on this year with Darius Kazemi, we handled the definition of “governance” like this:

…we take a broad view of governance, inclusive of all the socio-technical norm-setting, policy making, listening, structuring, management, and other forms of steering that are intended to keep Fediverse servers on course and afloat.

We explicitly included the way server teams manage themselves, including whether or not they build in redundancy on their teams and how they make financial, cultural, and technical decisions—including the many big and small decisions that increase (or decrease) stability and sustainability, shape diplomatic relations, and define moderation practices. And these decisions, more than any other factor, shape the fediverse that any given person will enter.

Let’s take the big one: “Remote moderation”—what Darius and I called “federated diplomacy” to emphasize its political character—has a huge effect on a member’s experience, but in ways that are largely opaque to new members.

When I'm on a platform like Twitter or Instagram or Bluesky, I know who can follow me and interact with me, and who I can follow and interact with: The default is "everyone on the network," and blocks and privacy controls (where they exist) allow for subtractions to that list. When I'm on the fediverse, those same questions—Who can interact with me? Who can I follow or interact with?—have much fuzzier answers. The usual answer, "Any account can follow any other account from any server" (with a silent "as long as user controls don't prevent it!" appended) isn’t actually true for most of the fediverse. Defederations—the technical execution of severed diplomatic ties—attempt to prevent interaction between servers and so define the landscape of possible connections, often in ways that are invisible to a member of a given server.

This is a necessary good for anyone who wants a fediverse experience that isn’t populated by griefers, spammers, trolls, and hate groups. The use of defederation for handling finer-grained conflict brings intense political complexity, but that’s the reality of collective self-governance. Taking governance decisions out of the layers of conflicting incentives and competing interests that make up platform corporations and putting them into the hands of individuals and small teams is political and messy, like any other society-building work.

It’s tempting to shove that messiness behind a potted plant when new people are coming over: let’s just get them in the door, right? And then they’ll understand. But hiding the political nature of the fediverse in service of simplicity puts new fediverse members at risk of falling into ill-governed spaces that make the fediverse needlessly nightmarish—or lonely, if they end up on a server that’s mass-defederated for sloppy spam controls or bad behavior.

It also makes it nearly impossible for them to understand how to have the best available experience for their specific needs.

Server leadership styles, policies, and practices also shape their members’ experience, as anyone who’s been on a server that flamed out or just disintegrated out of neglect can attest. Servers that run themselves as cooperatives or even along informally collaborative lines will ask different things of their members, and can also provide ways for members to actively shape a better experience for themselves and others. Governance includes sustainability work, too—sustainability as in money but also as in un-stressed moderation teams and redundant decision-making capacity for when someone gets hit by a figurative bus.

Who knows this

How much of everything discussed above is intelligible to potential new fediverse members? I would argue that the answer is “just about none of it.” Unless you have friends already on the fediverse to advise you, it’s almost impossible to tell what really matters in server choice, let alone how to determine which servers provide what kinds of governance. Let’s recap from the first post in the series:

- New and potential fediverse members don’t know to care about governance to begin with;

- if potential members do know to care about that, it’ll still be nearly impossible for them to understand what their specific fediverse governance needs are without guidance;

- and further, if they do understand what their governance needs were, they’ll still find it difficult to understand what different servers really offer, in terms of governance/moderation/leadership, especially given that servers with very similar public rules may actually govern their servers in quite different ways.

So how do we fix it? I think probably more than one way, if at all. And probably by starting with people and their needs and capabilities, rather than by reshuffling available but inadequate structured data.

I’ll start with a project I know I can contribute to, beginning with a survey of existing work and some user research with potential fedi members, existing members, and server teams; continuing through a couple of rounds of analysis and community validation; and ending with a few concise recommendations for a few different groups of people and a prototype to kick around. More on that soon.

Notes

Network commentator L. Rhodes' "Politics on fedi" brushes by some of this stuff from a different angle, especially in its introduction.

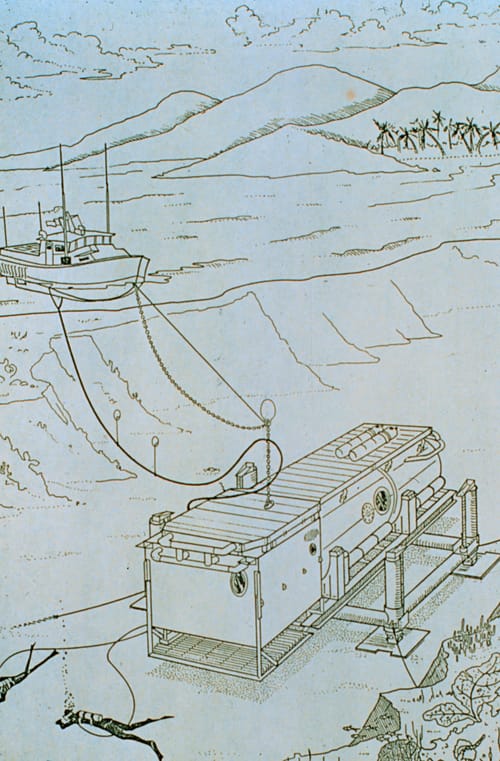

The featured image in this post depicts the Aquarius undersea lab in its first location in St. Croix, part of the US Virgin Islands. Image credit to OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP); Fairleigh Dickinson University; it appears here courtesy of NOAA's digital collections. (NURP!) Aquarius is an absolute delight and you can learn more about it over here. It was refurbished in 1990 and has been redeployed to the extraordinary Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Lastly, genuine and enormous thanks to the people who have signed onto this weird quest I have undertaken. Your signups and memberships are giving me so much hope for this model—and also so much optimism about how many people actually do care about this network culture work. It's been astonishing to see people throw in and I am deeply grateful for both the material and spiritual support.

(You can sign up for free emails or a paid membership here. Characteristic overthinking about the meaning of membership is this way.)