In the game of Go, bad shape is the term for configurations of stones on the game board that are inefficient in achieving their offensive goal (territory capture) and unlikely to achieve their defensive goal (the state of "life"). You can extend a bad shape in a fruitless attempt to make it better, but you'll generally be wasting your time.

The idea I keep coming back to is that the big platforms, like Marley, were dead to begin with, and are now something particularly bad, which is dead on their feet. Not because they’re been abandoned by users (yet) but because they’re structurally incapable of governing the systems they made, and most of the things they try to do about it introduce more and weirder problems.

While they were still gobbling hundreds of millions of new users each year—and while the old political machines were still catching up—platforms could outrun the problem. Now, though, the number of remaining uncaptured humans dwindles, the politicians and propagandists have adapted to exploit the mass-scale machinery the platforms provide, and the positions platform companies have contorted themselves into trying to shoehorn governance into ungovernable structures are increasingly hard to maintain.

Facebook especially is likely to zombie-shamble along for some time, held upright by its deep weave into the coordination of offline life and by the communities for whom it serves as a sole accessible connection to the internet, but the whole apparatus looks increasingly precarious.

(These are very simple points, but it remains a wince-inducing faux pas to say them in a lot of tech-thinking spaces, so I will keep pushing on the obvious.)

The evidence of the past decade and a half argues strongly that platform corporations are structurally incapable of good governance, primarily because most of their central aims (continuous growth, market dominance, profit via extraction) conflict with many basic human and societal needs.

As entities, large social platforms continuously undergo rapid mutations in service of their need to maximize profit and expansion while minimizing the kinds of societal and individual harm that can plausibly cause them regulatory trouble or user disengagement. (The set of things that can cause trouble is also always shifting, as political and cultural spheres influence and are influenced by the platforms.) But platform mutations emerge only within a narrow range of possibilities delineated by the set of decisions considered valid in, roughly speaking, Milton Friedman's model of corporate purpose.

Within this circumscribed mutation zone, certain goals are able to be named and earnestly pursued ("stop spam" or "eliminate the distribution of CSAM"), even if they're never achieved. Other goals (anything to do with hate speech, incitement to violence, or misinformation, for example) can be named and pursued, but only in ways that don't hinder the workings of the profit-extraction machinery—which mostly means that they come in on the margins and after the fact, as in "after the fact of a genocide that Facebook had years of explicit advance warnings about." Working on the margins and after the fact still matters—less damage is better than more damage—but it means "trust and safety" is kept well clear of the core.

Again, this is all simple and obvious. A tractor structurally can't spare a thought for the lives of the fieldmice; shouting at the tractor when it destroys their nests is a category error. Business does business. The production line doesn't stop just because a few people lose fingers or lives. And what is a modern corporation but a legal spell for turning reasoning beings into temporarily vacant machines? We know this, which is why we have OSHA and the FAA and the FTC, for now.

It's no surprise that when prodded by entities with cultural or regulatory power, platforms build more semi-effective AI classifiers, hire more underpaid contract moderators, and temporarily stiffen their unevenly enforced community rules, but then immediately slump back toward their natural form, which appears to be a cartoonishly overgrown early-2000s web forum crammed with soft targets and overrun by trolling, spam, and worse.

It’s possible to make the argument that sufficiently strong leadership could make even a tech corporation appear to be capable of holding an ethical line, and maybe even capable of accepting slightly smaller profits in service of socially beneficial goals—and that, conversely, the awful people in charge are the main source of the problems. It’s not a very good argument, though, even when I make it myself.

Yes, X is currently controlled by a bizarrely gibbering billionaire with obvious symptoms of late-stage Mad King disease. Yes, Facebook and Instagram—which control vastly more territory than X—are controlled by a feckless, Tulip-craze-mainlining billionaire with a long history of grudgingly up-regulating governance efforts when under public or governmental pressure and then immediately axeing them when the spotlight moves on. But would these platforms inflict less damage if they were led by people who valued the well being of others? Probably yes, to a degree. Twitter/X has offered a lurid natural experiment, and the changes in X after it moved from Jack Dorsey’s spacey techno-libertarian leadership to Elon Musk’s desperately needy quasi-fascist circus act have been obviously bad. A version of Meta founded and led by someone with a reasonably sharp ethical grounding clearly wouldn’t look much like the real Meta at all.

On the other hand, TikTok’s social function is reasonably close to Meta and X’s, and the fact that its CEO, Shou Zi Chew, seems like a relatively normal person, doesn’t seem to have correlated with dramatically better performance in eliminating Nazi organizing, genocidal and violence-inciting content, CSAM distribution (archive link), or the kind of semi-pro disinformation that makes it harder for people experiencing natural disasters to understand what’s happening.

Crucially, more reasonable CEO behavior doesn’t seem to prevent the lower-level and potentially even more destructive social effects of platforms that Henry Farrell persuasively explains from a social theory perspective, or that Renée DiResta memorably calls a “Cambrian explosion of subjective, bespoke realities” in Invisible Rulers.* (I'll do a separate post collecting thoughts on this angle, because it's too important to breeze by.)

The realities of our moment also work against arguments for the potential of heroic leadership: even apparently level-headed tech executives now appear to understand that the next Trump Administration intends to rule unreasonably and vengefully, and that failure to perform obeisance and make tribute may result in federal interference that could plausibly unmake their companies.

Those are not risks any global corporation can take, but our oddball lineup of big platform companies is in a special bind. No matter how desperately they want to be seen as neutral utilities, they have functioned, for good and ill, like social and political wrecking balls—and real or feigned misapprehensions about algorithms and censorship notwithstanding, real-world governments understand this. The second coming of Trump makes the situation especially stark, but the underlying dynamics are neither new nor temporary.

Given that every large platform posing as a public square has put itself into the genuinely untenable situation of acting as a global corporate arbiter of politically hot speech, they will all always be in the gunsights of the world’s least reasonable governments. This was bad enough for the platforms when the least reasonable governments were Putin’s or Erdoğan’s or Modi’s—a truly unreasonable government in control of their home jurisdiction is an existential threat.

And again, in reality, the corporations are configured to try to address the least political kinds of abuse—CSAM, spam, scams, and a few other forms of inauthentic behavior—and very little else. As a result, they can’t govern more subtle or politicized speech for much longer than I can roll a quarter down a piece of string.

So what would it take for a corporation to become capable of good governance of things like political speech, incitement to violence and genocide, hate speech, most forms of inauthentic behavior, and platform manipulation? Two things, at least:

- The ability and willingness to take and hold ethical stances that will be sharply unpopular with large swathes of the people mostly likely to effectively target them with legislation and abuses of power, and

- the ability and willingness to devote something approaching the majority of their company’s time, money, and attention to building and running devolved or federated systems for doing high-performance high-context local governance according to those unpopular ethical stances.

Can you bring yourself to imagine—concretely and in detail—these conditions occurring in the leadership of a global corporation?

And again, achieving a mode of governance that can appropriately handle those most obvious elements—the hate speech, the network abuse, the inauthentic behavior, all of it—is necessary but not sufficient for reaching something like a healthy equilibrium. The elements of big social platforms that make them attractive and fun and profitable are the same elements that, as currently implemented, turn low-level human behavior patterns around status, belief, conformity, and predation into a high-speed mass-scale mess of fractured publics and realities.

Two points of clarification: First, I’m not saying “Can’t fix people problems with technology,” which is exactly as true and useful as “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” (I used the former in what I thought was a very obviously sarcastic way, but apparently the intent was insufficiently clear.) If a technological system makes human problems worse, you have to fix the system or break it and build a better one.

Second, none of what I’m trying to get at here is about the intent of people who work on big platforms. Corporate platform trust and safety staff routinely work themselves to the brink of individual illness or collapse to handle what they’re permitted and resourced to handle—which is itself a tiny fraction of what would be necessary to handle to make platforms good. Corporate platform governance by technology companies whose success requires growth and attention-extraction, though, is a bankrupt idea.

If we briefly isolate the reality of our technological present, it’s hard to find it anything but absurd to expect a corporation to govern global or even local speech for any humanist value of “well.” And no one chose it, exactly, it just happened when the fantasies of the internet as an Apollonian zone of libertarian splendor met the reality of globally connected primate brains under late capitalism. I explicitly blame the connected-computer dream of technologically mediated liberation as cartoonishly exemplified in JP Barlow’s Declaration, which centered on keeping the bad old world of human governance, which it equated with censorship, out of the internet:

You claim there are problems among us that you need to solve. You use this claim as an excuse to invade our precincts. Many of these problems don't exist. Where there are real conflicts, where there are wrongs, we will identify them and address them by our means. We are forming our own Social Contract. This governance will arise according to the conditions of our world, not yours. Our world is different.

The governance arose, all right, once the money got real.

The computer dream’s rapidly evaporating and over-salinated shallows are still keeping the tech industry’s dumbest boats afloat, but the platforms have been scraping bottom for years while their owners slap on layers and layers of patches and bilge-pumps and bucket brigades manned by people from former colonies. The problem isn't (just) turning fact-checking on or off or deactivating a swarm of halfassed AI classifers or ceasing to pretend to act on most reports of misconduct, it's bad shape.

All of which is to say that yes, Zuckerberg is a terrible chump and Musk is a grotesque quasi-Rasputin, and that does matter, but the boards they stand on have been rotten the whole time. Centralized corporate governance of global mega-platforms was always a goofy idea, and we should have given up on it years ago.

This is where I get into awkward situations with lovely people, including several I count as friends, because they’re determined "not to let platforms off the hook.” I feel this, deeply, along with things like send the Sacklers to the guillotine. But keeping the fucked-up mutant fish on the hook will not magically transform it into an entity capable of governing.

—

Earlier this week at Platformer, Casey Newton reported some insider views on what Meta’s most recent roll-back of content moderation and fact-checking means. The post is worth reading, and after the Myanmar research I did in 2023, and for what it’s worth, I don’t think Casey’s sources overstate the dangers inherent in what Meta’s doing: more real human beings are going to suffer and lose children and be killed because of this. But I want to look at something in the cursory background section of the newsletter, about the work that Meta put in after 2016, when Facebook got criticized for hosting election-interference ops in the US:

Chastened by the criticism, Meta set out to shore up its defenses. It hired 40,000 content moderators around the world, invested heavily in building new technology to analyze content for potential harms and flag it for review, and became the world’s leading funder of third-party fact-checking organizations. It spent $280 million to create an independent Oversight Board to adjudicate the most difficult questions about online speech. It disrupted dozens of networks of state-sponsored trolls who sought to use Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp to spread propaganda and attack dissenters.

According to Financial Times reporting (archive link), Meta currently employs or has contracted with about 40,000 people to work on “safety and security,” of which just 15,000 are content moderators, for a user base of roughly four billion users, which works out to more than a quarter of a million users per moderator. This chimes with New York Times reporting (archive link) suggesting that in 2021, Accenture was billing Facebook for about 5,800 full-time contract moderators. (For what it’s worth, in 2017, Meta promised to add all of 3,000 trust and safety staff.) Nor are Meta’s moderation resources allocated evenly: About 90% of Facebook users are outside the US and Canada; that overwhelming majority gets approximately 13% of the company’s moderation time (archive link).

And while we’re here, in 2020—the year Oversight Board started hiring—Meta cleared about $91 billion in profit. The Oversight Board trust got $280 million from Meta, or just over 0.3% of the company’s annual profits. The Oversight Board itself, though inclined to deliver thoughtful if glacially slow recommendations, appears to have accomplished remarkably little.

Again: The work tens of thousands of people around the world put in to try to make platforms less terrible is real and essential work, and it’s often done at a terrible cost. It’s also the barest gesture at serious governance, and much of it is pure Potemkin Village.

That’s only a couple of things pulled from one paragraph that happened to hit my inbox while I was drafting this post, but I did a whole lot of that kind of close reading in 2023, and came out believing that platform intensifications of governance in response to periodic governmental pressure are best understood as a little bit of real (though deeply inadequate) change and a whole lot of flopping. Then, when the pressure comes off, the platforms re-orient like compass needles tossed into in an MRI machine.

—

Barlow’s Declaration—which is excruciating and which I’ve been making myself reread annually for years as penance for participating in tech culture—ends like this:

We will create a civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace. May it be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.

What we got instead was a handful of global-scale company towns that continue to prove their comprehensive unfitness to govern and their absolute vulnerability to the offline governments the free internet was meant to work around.

So sure: Protocols over platforms. Then we have to actually do the inelegant, un-heroic, expensive work of rebuilding the essential structures of human civilization on top of the protocols, because it turns out we just have the one world, online or off, no way out.

Thank you

This post, like the others on this site, exists because people have signed on to support the work. If you find it useful, and your situation allows for it with ease, please consider signing up! Enormous thanks to those of you who have. And a note to members: I've wrestled down the Ghost commenting problem and the first real discussion post for project members goes up tomorrow, so if you've signed up for a paid membership, look for that in your inbox soon.

Notes

* Renée’s book is very good and I recommend it for its lucid explanations and commitment to drawing on previous eras of mass communication without doing too deeply into either theoretical or historical rabbitholes (which I love, but which don’t make for popular reading). I don’t 100% agree with her conclusions, but they’re clearly stated and cleanly argued, which allows for productive disagreement—and I value that more than full alignment.

A common response to the things I've been posting is "Okay, but what will work, then?" I think there are hints at answers in the very chunky fediverse governance research I worked on last year, in online and offline cooperatives, in Rudy Fraser's Blacksky, and in the kinds of projects Nathan Schneider assesses in Governable Spaces. I'll continue to explore what I think might be good shapes for governance here in ways that—I hope—will be more pragmatic than quixotic.

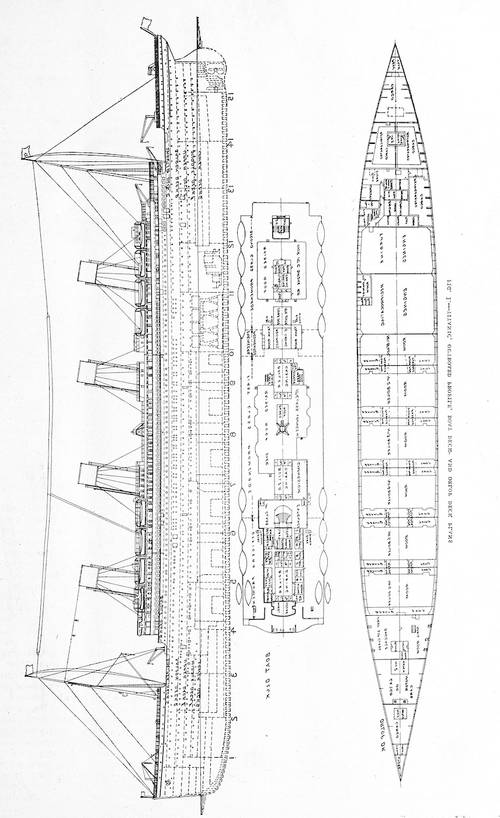

The featured diagram for this post is International Marine Engineering's 1912 depiction of the profile and deck of the Titanic (v. 17, p. 199).